Digestive symptoms often appear years before tremor in Parkinson’s disease, and growing evidence suggests the gut-brain axis may play a critical role in early disease processes and symptom management.

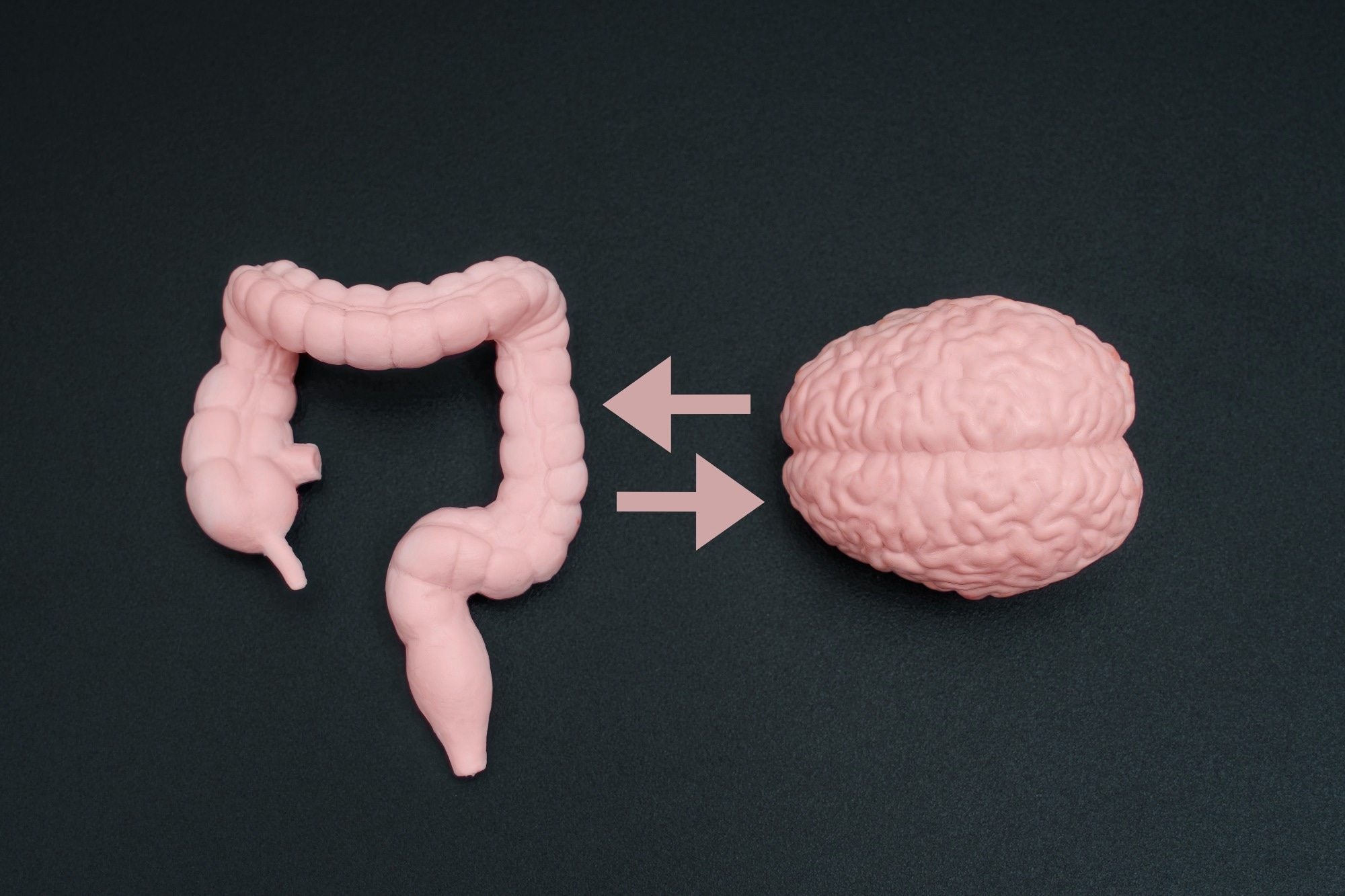

Study: Gut-Brain Axis: The Role of Gastrointestinal Issues in Parkinson’s Disease. Image Credit: Chizhevskaya Ekaterina / Shutterstock

In a recent review published in the journal Integrative Medicine, a group of authors examined how gastrointestinal (GI) disturbances and the gut-brain axis are associated with and may influence the onset, progression, and management of Parkinson’s disease (PD).

Background: Digestive Symptoms as Early Clues

Nearly 80% of people with PD experience digestive problems, often years before tremors or stiffness appear. Chronic constipation is a daily challenge for many patients even before a neurological diagnosis is made, raising the question of whether aspects of the disease process begin outside the brain.

Traditionally, PD is characterized by problems with movement, but growing evidence recognizes the GI tract as an important early site involved in disease-related changes. Intestinal and brain health are connected through the gut-brain axis, and further studies are needed to determine whether correcting gut imbalance can modify disease-related pathways or clinical outcomes.

GI Dysfunction as an Early Symptom of PD

PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder most commonly associated with motor symptoms such as tremors, rigidity, and slowed movement. However, non-motor symptoms, particularly GI disturbances, are now considered integral and early components of the disease.

Constipation, delayed bowel transit, and incomplete evacuation frequently appear many years before movement symptoms emerge. These early digestive changes are not simply side effects of reduced mobility but reflect underlying disease-associated processes.

Lower GI symptoms occur in approximately 70 to 80% of individuals with PD and substantially reduce quality of life. Impaired gut function can also disrupt the absorption of medications, especially levodopa, leading to variable symptom control and fluctuating therapeutic response.

These clinical challenges highlight the importance of understanding GI dysfunction, not only for early detection but also for optimizing disease management.

The Gut-Brain Axis and the “Bottom-Up” Hypothesis

The gut-brain axis is a bidirectional communication system linking the GI tract and the central nervous system through neural, immune, and metabolic pathways. The vagus nerve connects the gut and the brain, and accumulating evidence suggests that in some individuals PD may follow a bottom-up pattern, in which pathological changes begin in the gut and later involve the brain.

Abnormal alpha-synuclein protein aggregates have been detected in the enteric nervous system years before motor symptoms develop, supporting the hypothesis that neurodegenerative processes can begin outside the brain.

From a patient perspective, this helps explain why digestive symptoms often precede neurological decline and why early GI changes deserve careful clinical attention, while recognizing that this model may not apply to all individuals with PD.

Gut Dysbiosis and Neurodegeneration

Gut dysbiosis refers to an imbalance in the composition and function of gut microbiota. In PD, the gut microbiome is often altered, with reduced levels of beneficial bacteria and increased abundance of pro-inflammatory microorganisms.

This imbalance can increase the production of microbial metabolites such as lipopolysaccharides, which are associated with inflammation.

Lower levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly butyrate, are commonly reported and may compromise gut barrier integrity, allowing inflammatory substances to enter the bloodstream and potentially influence the brain.

These processes are associated with, rather than proven causes of, neuroinflammation and neuronal injury and may help explain observed links between gut health and both motor and non-motor symptoms, including fatigue and cognitive decline, in people with PD.

Constipation, Serotonin, and a Vicious Cycle

Constipation is one of the most common and persistent symptoms in PD and plays a central role in gut dysbiosis. Slowed bowel movements alter the intestinal environment, allowing pathogenic bacteria to thrive while beneficial microbes decline.

This imbalance can further worsen constipation, creating a self-perpetuating cycle.

Serotonin, a neurotransmitter involved in mood and gut motility, is largely produced in the GI tract, with approximately 90-95% synthesized by enterochromaffin cells. Gut bacteria play an important role in regulating serotonin production.

In PD, reduced gut motility and dysbiosis are associated with altered serotonin signaling, which may impair intestinal movement and nutrient absorption.

As a result, deficiencies in nutrients such as vitamin B12 and iron may occur in some individuals, particularly in later disease stages or in those with longstanding GI dysfunction, potentially affecting neurological health and resilience.

Neuroinflammation and Disease Progression

Chronic GI dysfunction is associated with sustained systemic inflammation, which is thought to contribute to PD progression. Increased gut permeability allows inflammatory molecules to enter the bloodstream and may compromise the blood-brain barrier.

This process can enable toxins and immune mediators to access the brain, activate brain immune cells, and contribute to damage of dopamine-producing neurons in brain regions affected by PD.

As neuronal loss progresses, both motor and non-motor symptoms worsen. However, GI dysfunction should be viewed as one contributing factor within a complex, multifactorial disease process involving genetic, environmental, and central nervous system mechanisms, rather than the sole driver of PD progression.

Integrative and Lifestyle-Based Interventions

Dietary and lifestyle interventions offer practical strategies to support gut health and potentially alleviate symptoms, although their disease-modifying effects remain under investigation.

Diets rich in fiber, antioxidants, and anti-inflammatory components can improve gut microbial diversity and barrier function. Adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet has been associated with reduced constipation, lower inflammation, and a lower risk of developing PD in observational studies.

Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics have shown promise in improving bowel function and modulating gut microbiota, including SCFA production, particularly in small clinical trials and pilot studies.

Regular exercise supports gut motility and has anti-inflammatory effects, while practices such as yoga and meditation may influence gut-brain communication.

Emerging therapies such as fecal microbiota transplantation are being explored as microbiome-targeted interventions, but they remain experimental and are not yet supported by standardized clinical guidelines.

Conclusion

This review highlights the GI tract's important role in the early features and progression of PD. GI dysfunction, gut dysbiosis, and altered gut-brain communication are closely associated with neuroinflammation and disease progression, although causal relationships remain unclear.

Evidence supporting the bottom-up model challenges traditional brain-centric views and underscores the importance of early digestive symptoms as potential warning signs.

Improving gut health through diet, lifestyle modifications, and microbiome-focused therapies may enhance symptom management and quality of life, but further research is required to determine whether these approaches can alter disease trajectory.

Continued investigation is essential to develop effective, personalized strategies for individuals and communities affected by PD.